The Growing Dilemma of Stored IVF Embryos

The increasing number of in vitro fertilization (IVF) embryos in storage has become a pressing issue for many clinics, not least because maintenance costs remain high and spatial constraints are becoming more pronounced. With more embryos being stored, the risk of human error also climbs, leading clinics to seek solutions to manage the burgeoning numbers of embryos that remain in a strange state of limbo.

The embryo boom

The conundrum largely stems from the soaring demand for IVF and the evolution in practices that have made the process more successful. "It's a problem of our own creation," says reproductive endocrinologist Pietro Bortoletto from Boston IVF in Massachusetts. The success of IVF today relies significantly on creating numerous excess eggs and embryos.

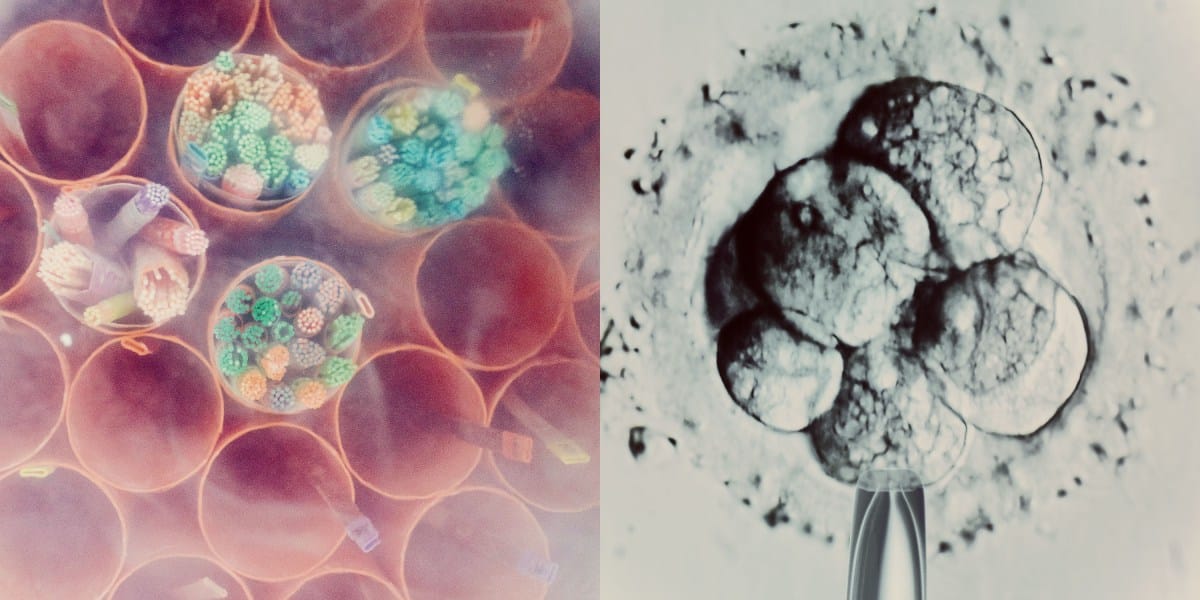

To optimize the chances of developing healthy embryos that can implant and result in successful pregnancies, clinics aim to collect several eggs. Patients undergoing IVF typically receive hormone injections to stimulate their ovaries, leading to the production of between seven to 20 eggs, instead of the usual single egg per cycle. These eggs are retrieved via a needle that accesses the ovaries through the vagina, and then fertilized in a lab, where approximately 70% to 80% become viable embryos.

These embryos are cultivated until they reach the blastocyst stage, roughly five to seven days after fertilization, at which point they are suitable for uterine transfer. However, only about 30% to 50% of embryos progress to this stage, leaving many patients with either no viable embryos or an excess, sometimes more than ten. Typically, only one embryo is transferred per attempt, with the remaining embryos frozen and stored.

IVF success rates have risen over time due in large part to advancements in storage technology. A decade ago, "slow freeze" methods were commonplace, often resulting in embryo damage. Current techniques involve vitrification, a rapid cooling method using liquid nitrogen that prevents ice crystal formation by turning water in embryos into a glass-like state.

Many clinics now favor a "freeze all" strategy, saving all viable embryos through cryopreservation and delaying transfers. This approach often accommodates genetic testing of embryos. Post-fertilization, embryos can undergo preimplantation genetic testing (PGT) around seven days old, which helps identify potential genetic issues.

This genetic screening is growing more prevalent in the U.S., rising from 13% of IVF cycles in 2014 to 27% by 2016. Embryos subjected to PGT must be frozen during the testing period, typically lasting a week or two, due to the inability to continue development until results are received.

Remarkably, there appears no limit to how long embryos can remain in storage. In a striking case, a couple in Oregon welcomed twins in 2022 from embryos that had been stored for 30 years, highlighting the longevity embryos can maintain under preservation.